Winold Reiss and the Challenges of Modernism

The extremely versatile German-American painter, designer, and teacher had once been celebrated as a "modern Cellini" in the United States by Du Pont Magazine (XXV, 3. March 1931). In the 1920s and 30s, he emerged as an influential figure in transatlantic encounters and modernist aesthetics. After his arrival in the US shortly before the outbreak of WWI, Reiss established his own Art School and Design Studio in downtown New York, organized a summer school in Glacier Park, Montana in the years to follow, and co-founded the art magazine Modern Art Collector. His works were widely exhibited and reproduced in magazines such as Century, The Craftsman, The Forum, Opportunity, Scribner’s Magazine, or The Survey Graphic. Beyond his work in portraiture and commercial design, Reiss was an accomplished designer who created elaborate mosaics in restaurants and other public buildings such as the Cincinnati Union Terminal. He collaborated with leading artists and intellectuals including Alain Locke, Katherine Anne Porter, Paul Kellogg, Miguel Covarrubias, and Langston Hughes. Among his students were Ruth Light Braun, who is known for her portraits of Jewish life in New York and Palestine, the mural artist Marion Greenwood and the African American key figure of the visual Harlem Renaissance, Aaron Douglas. Despite Reiss’s impressive range of creativity, however, his rich work of ethnic portrait paintings, distinctive interior modernist design, and cutting edge graphic designs has been relegated to the footnotes of American art history. In Germany, Winold Reiss is hardly known at all. The last exhibition of his artwork was in 1937 in Berlin with a special focus on his Indian portraits.

|

|

|

|

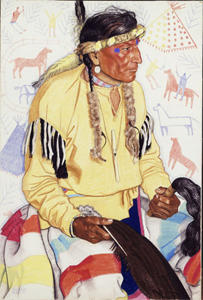

W. Reiss, Lazy Boy in His Medicine Robes. 39" x 26", mixed media on Whatman board, 1927. Reiss Archives |

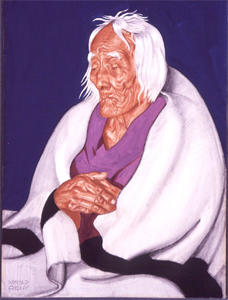

W. Reiss, Eagle Head. 30" x 22", pastel & tempera on Whatman board, 1928. Reiss Archives. |

While the paintings of Reiss's student Aaron Douglas continue to dominate the discussion of portrait art in the Harlem Renaissance, Winold Reiss’s efforts to promote the recognition of African American culture have received comparatively little attention. Richard Powell, however, asserts that Reiss provided the "classic images of the period" and "perfectly captured the common ground from which these newest structures and racial pre-occupations sprang" (Black Art: A Cultural History. London: Thames and Hudson, 2002. 42). Reiss's transatlantic connections, contributions, and democratic vistas are less visible today than half a century ago. For example, only the first edition of Locke's manifesto of the Harlem Renaissance features fourteen of Reiss's color illustrations of leading members of the New Negro movement. Later editions only reprinted his black and white decorations losing much of his innovate foray into a bold use of color which he had brought from his training at the Royal Academy of Arts in Munich. The re-edition of The New Negro from 1992 eliminates several elements of Reiss's graphic design and all of the color portraits. Amy Helene Kirschke's analysis of Aaron Douglas's mural artwork in "The Fisk Murals Revealed" emphasizes the "flat style of synthetic Cubism and Matisse" and especially "the work of the European painters Robert Delaunay and Frantisek Kupka and the American Stanton MacDonald Wright" (Aaron Douglas: African American Modernist. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007. 116). However, it falls short of addressing the obvious significance of the role that the German immigrant artist and Douglas's mentor, Winold Reiss, played in defining the nature of African American art in the 1920s.

|

|

|

|

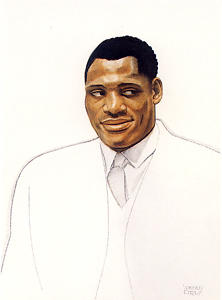

Ill: W. Reiss, W.E.B. Du Bois, Paul Robeson, pastel on Whatman board 30" x 22", 1925. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C |

|

In her seminal publication The Great American Thing: Modern Art and National Identity, 1915-1935 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), Wanda Corn has speculated that Reiss’s work may indeed embarrass scholars. Recent scholarship on the Harlem Renaissance such as the publications of George Hutchinson (e.g. The Cambridge Companion to the Harlem Renaissance. Cambridge University Press, 2007) or Sieglinde Lemke (Primitivist Modernism: Black Culture and the Origins of Transatlantic Modernism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998) has shifted its focus from individual figures to racial interactions, crossovers, and transatlantic interchanges. Caroline Goeser has brought attention to Reiss’s ground-breaking illustrations for book covers within a comprehensive comparative analysis (Picturing the New Negro: Harlem Renaissance Print Culture and Modern Black Identity. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2007). Since 1986, the Prints and Photographs Division of the Library of Congress has acquired over 465 drawings and prints by Winold Reiss that are now included in its "Winold Reiss Design Collection."

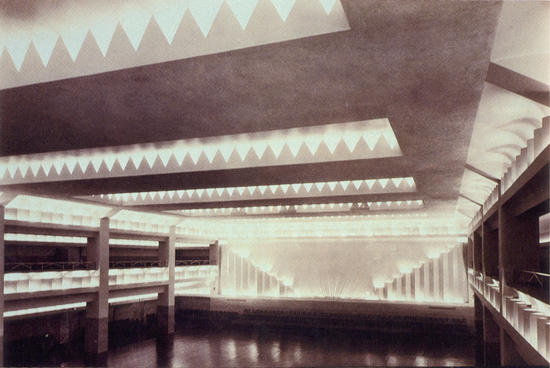

Ill.: W. Reiss, Design for the Ballroom, Hotel St. George, Brooklyn. Photograph, ca. 1930. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

“Cultural Mobility and Transcultural Confrontations: Winold Reiss as a Paradigm of Transnational Studies” will rethink Reiss’ role in the visual representation of ethnic American identities. The symposium builds on, and goes beyond the ground breaking work of Jeffrey Stewart, who introduced a selection of Reiss's portraits in the 1989 exhibit "To Color America" at the National Portrait Gallery of the Smithsonian Institution. The European artistic background that Reiss brought to the American scene demands a specifically interdisciplinary and international perspective. Philip McMahon suggested in his review of Reiss’s book You Can Design (published in 1939) that echoes of Europe could even been seen in the works of his students, echoes transformed and diluted by time and distance in their transmission from the Old to the New World. Reiss’s visual narrative of American ethnicity revealed a German element woven into its fabric. In order to critically reassess his work in different media, in the fine arts and commercial design, the symposium takes the recent manifesto on Cultural Mobility by cultural critic Stephen Greenblatt as a guide to reassessing the complexity of the German-American experience encoded in Reiss's art. The conference will thus consciously transgress the usual art historian's discipline in order to shed light on contact zones arising from intercultural migration and the exchange of cultural as well as artistic ideas. From such a perspective Winold Reiss emerges as a cultural "mobilizer," who in the sense of Greenblatt can be understood as an agent, go-betweener, translator, and intermediator. Symposium speakers will address questions of international exchange, processes of intercultural translation, and moments of transcultural confrontations in order to rediscover the life and oeuvre of the German-American artist Winold Reiss.

F. Mehring