History & Traditions

History of the John F. Kennedy Institute

by Kian Riedel

In 1986, a conference at the Aspen Institute in Berlin evaluated whether the John F. Kennedy Institute (JFKI) at the Freie Universität should continue. Originally conceived as a liberal, interdisciplinary project promoting democratic ideals, the institute had made headlines in the previous decade that appeared to contradict its mission.

By 1974, a Freie Universität publication had asked: "John F. Kennedy Institute - Auxiliary School of Marxism?" The institute, initially intended as a European center for academic engagement with the U.S. and a model for translating the workings of a functional democracy to postwar Germany, faced allegations of being run under Stasi influence and by radical leftists who outnumbered the professors on the institute's council.

In response to the 1968 student movement against authoritarianism, the Freie Universität had implemented one of the most democratic university laws worldwide, providing students significant participation rights in its decision-making processes. This led to political gridlock at the JFKI, where academic excellence was occasionally sidelined by personal politics.

While the headlines may have amplified the students' ideological motivations, these prolonged debates underscore the JFKI's struggle during the 20th century to balance critical engagement, democratic values, and productive research and teaching in a city as influenced by Cold War politics as Berlin.

The following pages delve into how the JFKI's inception was tied to Cold War politics, how its institutional setup aimed to unite diverse perspectives on the U.S., and how the gridlock was ultimately resolved. The result was a balance between critical inquiry and academic proficiency, as initially envisioned by its founder, political scientist and University of Chicago-educated Jewish emigree Ernst Fraenkel – a success story in the end.

1 The postwar years and the foundation of the America-Institute

Ernst Fraenkel's 1962 concept of American studies was grounded in his belief that understanding a country's political system required insights into its economics, society, and culture. This approach built on Berlin's long-standing tradition of studying the U.S. and other nations from multidisciplinary perspectives. In the 1930s, the Nazis had degraded this original research setup to a propaganda science focused on studying the enemy.

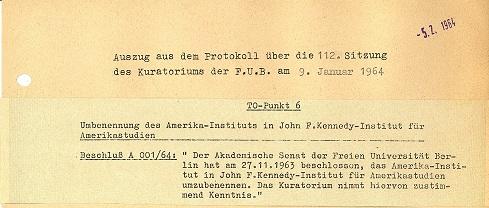

The America-Institute was established in 1963 as an extension of the American literatures section of the English Studies seminar at Freie Universität. Until that time, this was the only way for students to engage with the protective power of Berlin, two years after the construction of the wall separating East and West Berlin.

The new institute benefited both financially and politically from its location in West Berlin. The Ford Foundation generously supported the creation of a North America-focused library, which was planned to be the largest of its kind in Europe. Given its location surrounded by communist territory, this had a symbolic significance and was in line with the missions of the America-Institute:

- to be a center of American studies, suitable for making available to scholars not only from Berlin and the Federal Republic of Germany, but from all European countries, the sources, materials and scientific literature necessary for useful scientific work on the various aspects of the overall phenomenon "USA", as well as to serve as a place for their cooperation;

- to develop a relatively small number of specialists in the Americas who strive to gain a historically in-depth insight into the intellectual, geographical, cultural, social, and political-economic structure of the United States through the integration of specialized studies in several disciplines of American studies;

- to provide a broad group of minor students with the knowledge of American literature, history, social and cultural studies that will enable them to overcome the many preconceptions that make understanding the United States so excessively difficult and to acquire knowledge that is essential to a better understanding of the United States and the issues that affect it than has been the case in the past.[1]

At the official opening ceremony of the institute, held in the gymnasium-turned-library of its new home on Lansstraße, the broad mission was reflected by the presence of several American dignitaries as well as the then mayor of Berlin, Heinrich Albertz. Among the attendees was Fraenkel, who had previously worked for the American State Department, undertaking several studies on the reconstruction of German academia after the war. Other notable guests included Dr. Eleanor Dulles and Dr. Shepard Stone, both American officials responsible for the cultural and scientific reconstruction of Berlin post-war. In his opening speech, Fraenkel acknowledged that without their support, the institute, which had been renamed the John F. Kennedy Institute in honor of the late American president in 1963, would not exist.

2 1970s radicalism, institutional gridlock, and a conservative reaction

At the opening ceremony of the decade, the spirit of protest was already evident through protest posters and students accompanying the Berlin mayor, who recently reduced university funding, to the JFKI. In the U.S., student protests focused on civil rights and the Vietnam War. However, in late 1960s and 1970s Germany, protests were against authoritarian structures and lingering remnants of fascism, including at the university.

The Freie Universität was central to the movement, and the JFKI became a stage where the dichotomies of young leftists and an older generation, survivors of National socialism, played out. The institute's close ties to U.S. army officials piqued the interest of the East German Stasi. Some institutional politics seemed to mirror the Cold War conflict between liberalism and socialism.

However, the politically diverse nature of professors and students led to proxy conflicts that distracted from the JFKI's actual research and teaching goals. While U.S. universities were still debating which version of the nation's history should be taught, the JFKI was already offering courses on African Americans and women in American literature. The first protest at the institute was a sit-in demanding the inclusion of a female author in the curriculum.

During this period, the Freie Universität's regulatory framework became one of the world's most radical academic experiments. Initially, the university followed the traditional German structure with professors as the ultimate decision-makers. The Berliner Hochschulgesetz, in response to the democratic demands of the student movement, gave the same voting rights to students, research assistants, and university staff.

Unfortunately, new hires became increasingly politicized to maintain this balance. One research assistant was asked during their interview how they would vote in a split decision - for the professors or the students. After siding with the students, they were hired. Another candidate who suggested that the content of the issue might also be important did not get the job. As a result, internal politics took precedence over the institute's actual task: to improve the understanding of the United States.

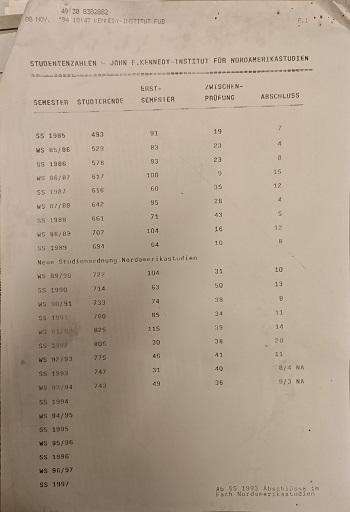

This task did not exclude critical inquiry, but the political divide at the institute solidified ideological views on the U.S. The gridlock in the institute's council made it difficult to improve research and teaching structures. The institute suffered a decline in resources and student numbers in the 1970s and 1980s. A group of conservative professors publicly criticized these issues, comparing them to Soviet methods in the humanities. This led to a conference on the potential closure of the institute at the Aspen Institute in Berlin in 1986.

Despite the alleged political beliefs of its members, the JFKI was not living up to its original goal of providing comprehensive insights into its subject matter. The university pragmatically broke the stalemate in the institute's council by creating five additional for professors; [2] in 1986, support from the university president and other North American Studies researchers enabled the JFKI to survive the Aspen Institute conference, ending a politically tumultuous time.

3 Interdisciplinary Cooperation and interdisciplinary success in 1990s and 2000s

The threat of closure served as a wake-up call. With the end of the Cold War and the unification of Berlin, the institute quickly attracted a growing number of researchers from the GDR and Eastern Europe.[3] Professors from various disciplines could finally unite their efforts in a streamlined research agenda in the newly depoliticized environment. By providing resources to researchers from all over world, the institute, as originally intended by Ernst Fraenkel, finally fostered meaningful analysis of U.S. society and state. This led to public recognition for its excellence and its ability to cater to all levels of higher education.

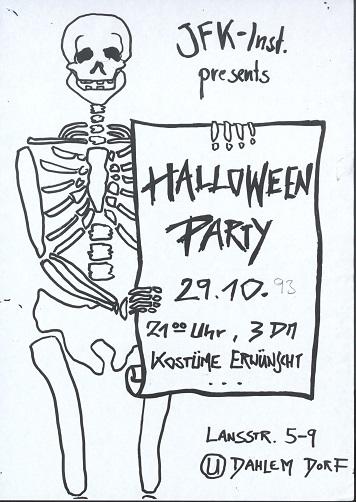

The unification of Berlin removed physical barriers, enabling the institute to become the primary resource for researchers in Europe interested in North American topics. Shortly after the wall fell, the institute welcomed an increasing number of colleagues from the East Berlin Humboldt University and other research facilities from Eastern Europe. The renewed interest in American topics, coupled with heightened academic productivity, led to a surge in student numbers at the JFKI. These students became known for their proactiveness, organizing events and activities that reached beyond the classroom.

|

|

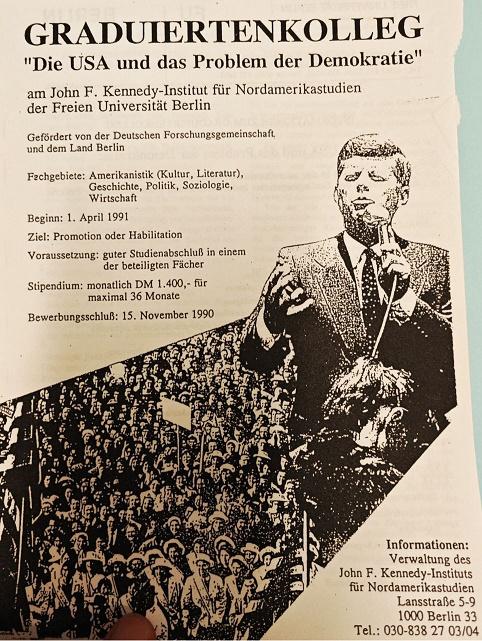

The termination of political polarization allowed professors and researchers to focus their energies on classrooms and their research. The 1990s saw a significant increase in the number of publications from the institute, and new connections with American research institutions were established. Regular visits from American and Canadian professors through the "Ernst-Fraenkel-lectures" and guest professorship grants encouraged intellectual exchanges at the institute. In 1989, a "Magister" program in North American Studies equivalent to a master’s degree in Germany was introduced, enhancing the institute's academic profile. Moreover, the newly founded "Graduiertenkolleg" in 1991 enabled students from diverse disciplinary backgrounds to complete postgraduate research projects focused on "The U.S. and the Problem of Democracy".Funded by the DFG, approximately 40 PhDs and habilitations were completed at the institute over a 10-year period. For the first time, the JFKI was able to cater to all levels of higher education, and its academic profile exceeded the political controversies of the past.

The 2000s brought many reforms to the JFKI, as well as its greatest success to date. In 2005/06, study programs were adapted to the Bologna process, allowing students to officially enroll in Bachelor and Master programs. Furthermore, the JFKI received as one of only two institutions not dedicated to the natural sciences funding for another postgraduate institution, the Graduate School of North American Studies (GSNAS), through the German federal Exzellenzinitiative in 2007. Recovering from financial difficulties in the 1990s, the new funds allowed for the development of a curriculum for initially 10 PhD students per year, complete with disciplinary and interdisciplinary elements and a dedicated administrative structure. The GSNAS was also able to regularly invite distinguished professors from North American Universities for a semester, contributing to lively debates at the institute and supervising PhD students in their individual projects.

In the 21st century, the JFKI fully embodied its internationalist spirit. While scholarships such as the Terra Foundation for American Art already had supported the presence of North American scholars, the new BA curriculum included a mandatory stay abroad for JFKI students. Fostered by the direct exchange program of the Freie Universität, students often returned to the institute with expertise and experience from top-notch North American research facilities. Additionally, the JFKI hosted a growing number of international conferences, with an annual international conference organized by a cohort of the graduate school featuring renowned guest speakers on current North American topics. From 2015 onwards, the MA program was taught exclusively in English, followed by a BA program in 2018. This attracted a growing number of international students, with more than half of the student body now coming from outside Germany.

Ernst Fraenkel's pluralistic theory of democracy made him one of the most significant political scientists in Germany in the 1950s.[4] The JFKI's history in the second half of the 20th century showcases the challenges of aligning diverging interests. Founded on another of Fraenkel's theories, that political science should be an integrative science, the JFKI was designed to host a multitude of perspectives, problem solutions, and interests. While the Cold War led to intense internal conflicts, this diversity of interests also proved to be a formula for success. The integration of diversity into academic output established the JFKI as a leading institution for the study of North America.

[1] Ernst Fraenkel, "Memorandum concerning the establishment of an inter-departmental America Institute at the Free University of Berlin", November 1962.

[2] Resolution of the board of trustees, 5/8/1974

[3] This had been the case before the fall of the wall, too, but in much lower numbers.

[4] Gerhard Köhler, Ernst Fraenkel – Leben und Werk, Vortrag zur Enthüllung der Fraenkel-Skulptur im John F. Kennedy-Institut, 12/14/1994.